Women in the Workforce

Advancing a Just Recovery in New York City

Published June 2022

About Our Organizations

A Better Balance is a national legal nonprofit advocacy organization that uses the power of the law to advance justice for workers, so they can care for themselves and their loved ones without sacrificing their economic security. Through legislative advocacy, direct legal services and strategic litigation, and public education, A Better Balance’s expert legal team combats discrimination against pregnant workers and caregivers and advances supportive policies like paid sick time, paid family and medical leave, fair scheduling, and accessible, quality childcare and eldercare. When we value the work of providing care, which has long been marginalized due to sexism and racism, our communities and our nation are healthier and stronger. Learn more at www.abetterbalance.org.

The Community Service Society of New York (CSS) has worked with and for New Yorkers since 1843 to promote economic opportunity and champion an equitable city and state. We power change through a strategic combination of research, services, and advocacy to make New York more livable for people facing economic insecurity. By expanding access to health care, affordable housing, employment, opportunities for individuals with conviction histories, debt assistance, and more, we make a tangible difference in the lives of millions. Learn more at www.cssny.org.

Executive Summary

In many ways, 2021 was an especially difficult year for women in the New York City workforce. The second year of an historic global pandemic continued to create new challenges for women. The economic downturn precipitated by the pandemic has been nicknamed the “she-cession”¹ and economists are predicting that, without intervention, it could take years if not decades to undo the setback to women’s economic gains during the still-ongoing pandemic.² While pandemic job loss continued to impact many people, women of color bore the brunt of the losses.³ Issues that long pre-date the pandemic were brought to the fore, as women continued to struggle to balance maintaining their economic security, and the economic security of their families, caring for their own health needs, and also struggling to meet the family caregiving needs that disproportionately fall to them, due to continued gendered expectations about the labor of caregiving.

Since 2002, the Community Service Society’s annual Unheard Third Survey, designed and administered in partnership with national polling firm Lake Research Partners has polled New York City’s low-income residents to understand their hardships and their views on the solutions that would be helpful to them. By asking questions regarding employment, benefits recipiency, housing, healthcare needs, financial livelihood, technology access and more, this survey provides a unique and vital window into the lives of low-income women as they navigate these conditions. Using the insights from analysis of the survey responses, we assessed the major challenges facing women in New York City’s workforce and provide, in this report, policy recommendations to ease their struggles.

New York State and New York City have long been pioneers in creating the legal infrastructure necessary to make it possible for low-income women to meet the too-often competing demands of work and family. This includes the passage of one of the first paid sick time laws in the country in New York City in 2013, the state’s paid family leave law in 2016, the recent passage of permanent and emergency paid sick time for the whole state. New York City made history with the groundbreaking passage of the Pregnant Workers’ Fairness Act in 2014 and the caregiver anti-discrimination law in 2016. And the creation of the Excluded Workers Fund in 2021 was a clear recognition of the needs of undocumented workers and families traditionally left out of most work and legal protections as well as emergency pandemic support.

The Unheard Third Survey data makes clear that there is more work to be done to build on these important protections. For instance, while New York recently made significant investments in childcare, we need even bolder action to bring about affordable, equitable childcare for all and value the work of childcare workers. We must ensure that low-income women in New York City have the support they need in the workplace to both survive the ongoing pandemic and to ensure an equitable pandemic recovery in which they can thrive at work and care for themselves and their loved ones.

Key Findings

The Unheard Third Survey found that New York City women experienced:

- Employment loss:

- 40 percent of low-income women suffered employment losses since the onset of the pandemic: Almost a quarter of these women had to drop out of the labor force entirely.

- Job loss rates were higher for women of color—around 38 percent of Black women and 36 percent of Latina/x women reported losing employment, compared to 30 percent of white women.

- Income loss:

- Even among women who continued working, nearly a third reported that their households experienced a reduction in hours, wages, or tips in the past year.

- Caregiving responsibilities:

- 25 percent of low-income women in the paid workforce reported that they needed to stop working for health and/or caregiving reasons.

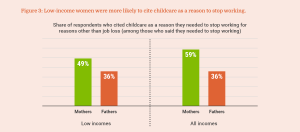

- Among parents who needed to stop working, 59 percent of mothers cited childcare concerns as the main reason compared to 36 percent of fathers.

Changes in nature of work:

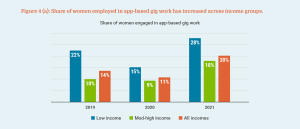

Changes in nature of work:- In 2021, 20 percent of working women reported engagement in app-based gig work in the past year—nearly double the 2020 rate of 11 percent.

- Lack of awareness regarding benefits:

- 55 percent of low-income women in the paid workforce had not heard about their right to paid sick time.

- 51 percent of low-income working mothers said that they had not heard about the paid sick time law, seriously undermining the law’s effectiveness.

- Critical but uneven safety net supports:

- Traditional and expanded safety net programs played a major role in alleviating the economic hardship of low-income households, although some of the households most in need did not receive assistance.

- Financial precarity:

- 42 percent of low-income women in New York City’s paid workforce have less than $500 in emergency savings, compared to only 19 percent of their moderate to higher income counterparts.

- 43 percent of low-income women in New York City’s paid labor force are worried all or most of the time about having enough income to pay the bills.

Key Recommendations

Low-income New York City women are struggling to balance the competing demands of work and care. This was true prior to the pandemic, but the ongoing public health crisis and the resulting economic downturn—which had a particularly harsh impact on women, especially women of color—has brought this work-care crisis into ever-sharper relief. In the third year of this ongoing pandemic, New York should use this past year’s lessons as a guide for building a path forward.

The pre-pandemic status quo—including inflexible schedules and overly punitive workplace environments for low-income workers, inaccessible and unaffordable childcare, and workers increasingly unable to meaningfully access the workplace rights to which they are entitled and workplace benefits, many of which they have paid for—enabled the pandemic to create such widespread economic devastation.

There can be no return to the pre-pandemic “normal”; instead, we should view the pandemic as an opportunity to see more clearly what workers truly need and to build a future that meets those needs. The Unheard Third Survey results make clear that urgent action is needed to enable New York City women to maintain their economic security while caring for themselves and their loved ones. This report recommends that New York State and New York City do the following:

- Expand outreach, education, and enforcement of city and state laws that safeguard workers’ rights and modernize notice to employees

- Ensure workers have increased access to fair and flexible schedules, alongside standard workplace protections and employer-provided benefits

- Modernize the State’s Temporary Disability Insurance and Paid Family Leave program

- Expand access to high-quality, affordable childcare

- Curb the use of overly-rigid, punitive attendance policies

- Expand app-based gig workers’ rights and ensure their access to standard workplace protections

- Protect caregivers from discrimination in the workplace

- Lead by example as model employers

As the pandemic continues, and as New York plans for the future, the needs of low-income women must be prioritized by our government and employers. New York has the opportunity to build on important existing workplace protections to assist low-income women as they weather the ongoing pandemic and make the post-pandemic future a brighter, more equitable one.

Background

Who Are Low-Income Women in New York City?

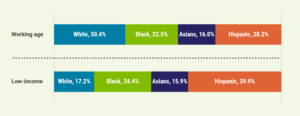

The 2.7 million women in the New York City workforce are still reeling from pandemic-related blows to their health, employment, earnings, and families. Of these women, the ones who are suffering the most are the one million women in low-income families, most of whom are women of color. It is critical to note that even pre-pandemic, women in the city’s workforce faced an unlevel playing field. The section that follows provides a pre-pandemic snapshot of the state of employment and earnings of low-income women in the workforce using the American Community Survey data. This snapshot is meant to provide a baseline with which to compare the state of the pandemic economy.

Pre-Pandemic Labor Market Realities of Women in Paid Workforce in NYC

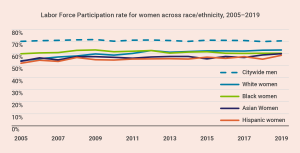

- New York City women’s Labor Force Participation rate, defined as the share of all women aged 16 years and up who are either employed or unemployed and actively looking for work, was around 60 percent in 2019, a full 10 percentage points lower than that of men. Labor force participation rates of Hispanic women were low relative to other groups, perhaps indicative of the widespread challenges, including discrimination based on race, gender, and immigration status, they face in engaging with the job market. (See Figure A3 in Appendix.)

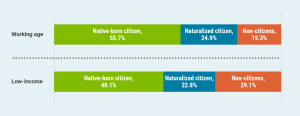

- A majority—83 percent—of low-income working women in New York City were from communities of color. (See Figure A1 in Appendix.) Low-income women were also more likely to be immigrants: while immigrant women were around 20 percent of the workforce, they made up around 30 percent of the low-income workforce. (See Figure A2 in Appendix.)

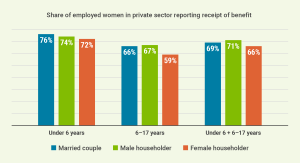

- One major impediment that prevented women from fully participating in the labor market was childcare: Irrespective of the age of the child, women who were heads of households with children were less likely to be in the labor force relative to both their male counterparts and their female counterparts in married couple households. (See Figure A4 in Appendix.)

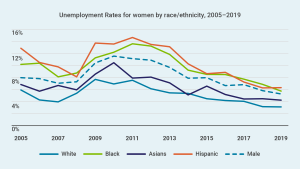

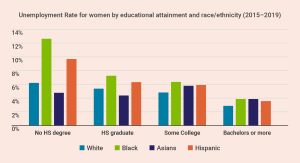

- In 2019, New York City women’s unemployment rates reached historic lows of 4.8 percent, 0.5 percentage points lower than the rate for men, but unemployment rates among the city’s Black and Hispanic women, and women in the Bronx, continued to be higher relative to citywide rates. (See Figure A5 in Appendix.) While women without high school degrees had the highest rates of unemployment, even within similar levels of educational attainment, Black and Hispanic women had higher unemployment rates than white and Asian women. (See Figure A6 in Appendix.)

Pre-pandemic Inequity in Earnings, Income and Employment

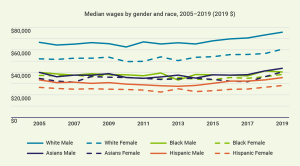

- From 2005 to 2019, women in New York City continued to earn less than men, and although the gap between median wages had begun to shrink over the first few years of the decade, those trends abated. Of note, Hispanic women continued to be paid low wages relative to non-Hispanic women as well as men of all races and ethnicities. (See Figure A7 in Appendix.)

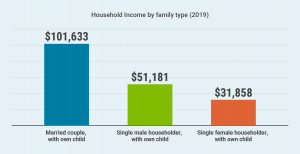

- The gap between men and women’s wages was reflected in differences in household incomes, especially between male- and female-headed households. Half of all female-headed households with a child/children earned less than $31,858 in 2019. Male-headed households with a child/children were much better off in terms of income, but both these household types were worse off than households where spouses (including unmarried partners) were present. (See Figure A8 in Appendix.)

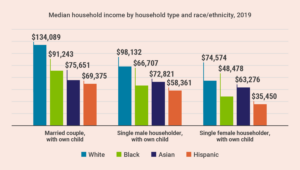

- Households led by single women of color had lower median incomes relative to their white and/or married women counterparts. Households with a child/children headed by single Latina women had median incomes of $35,450. This income put them barely above the poverty threshold using the City’s NYC.gov Poverty Measure: for 2019, the poverty threshold for a 1-adult 2-child household was determined to be $30,097.4 (See Figure A9 in Appendix.)

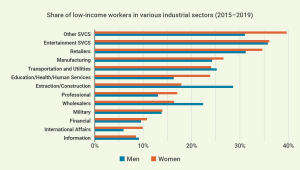

- That women were paid less than their male counterparts, on average, was partly due to the kind of industries and occupations where women were—often due to occupational segregation and gender stereotyping—disproportionately represented. Women tended to be overrepresented in industries that pay lower wages.

- For instance, the education, healthcare and home care services sector employed around a million workers in New York City; three-fourths of those employees were women and a quarter of them were low-income. Personal care and other services was another industry where women made up the majority of the workforce and approximately 40 percent were low-income. Other major industrial sectors in which low-income women comprised over a third of the women in the industry are retail and leisure and hospitality, both employing around 181,000 women. (See Figure A10 in Appendix.)

With this backdrop in mind, we turn to the findings from the Unheard Third Survey and the key policy recommendations that follow from the analysis.

Findings from the 2021 Unheard Third Survey

Jobs, Wages, and Work

Job recovery among women remains sluggish, with low-income women and women of color continuing to bear brunt of pandemic-related job and income loss

In 2021, more than a third of women reported that they had experienced temporary or permanent job loss in their household since the start of the pandemic. (See Figure 1.) While low-income women have seen some improvement in household job loss rates in 2021 compared to 2020, the job loss rate among low-income women remains high at twice the pre-pandemic rate of 20 percent.

Figure 1: Rates of job loss much higher among low-income women5

While women across all racial/ethnic groups saw a dramatic increase in temporary or permanent job loss in their households between 2019 and 2021, Black and Asian women experienced the most increases in job loss. As seen in Figure 2, 38 percent of Black women reported job loss in their household in 2021, about three times higher than the share in 2019 with job loss.

Furthermore, recent research from the National Women’s Law Center found long-term unemployment rates (defined as being unemployed over 26 weeks) have been higher among Asian women than average, and higher than for Black and Latina women.6 This is indicative of the fact that while Asian women might have low unemployment rate overall, those among them who have been unemployed face a particularly difficult struggle to get back into the paid workforce.

Figure 2: Low-income Black and Latina/x women had higher rates of temporary or permanent job loss.

Even among women who were able to keep their jobs, a rising share experienced pay cuts in the past year: in 2021, nearly a third (32 percent) of women in the paid labor force, including 31 percent of women in high-income households, reported that they or someone in their household experienced a reduction in hours, wages or tips in the past year, up from 16 percent in 2019.

Moderate to higher income women were more likely than those with lower incomes to report a shift toward remote work

More than half of moderate to higher income women in New York City’s paid labor force said that they switched to working from home, compared to only 35 percent of low-income women. Since the ability to work remotely is closely related to the type of industry in which the worker is employed, it is unsurprising that a majority of low-income women were unable to make the switch.

Low-income women in the paid workforce are more likely to work in industries that necessitate in-person interaction, such as food service, transportation, hotel, construction and arts and entertainment. (See Figure A10 in Appendix). Given that the in-person interaction required in these industries often puts workers at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19, it’s not surprising that more than half (53 percent) of low-income women who needed to stop working for reasons other than temporary or permanent job loss cited health or a disability as a reason—suggesting that both the need to care for others (including vulnerable members of one’s household), and also the need to care for oneself, were key drivers of women’s job loss during the pandemic.

Impact of caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic

Low-income women in New York City were two times more likely than those with moderate to higher incomes to report that they needed to stop working for reasons other than temporary or permanent job loss (25 percent of low-income women vs. only 11 percent of moderate to higher income women). Among parents who said that they needed to stop working for reasons other than job loss, 59 percent of mothers cited childcare concerns as a reason, compared to 36 percent of fathers. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: Low-income women were more likely to cite childcare as a reason to stop working.

Rise in app-based gig work among working women across incomes and racial/ethnic groups

Women’s participation in the city’s app-based gig economy increased across incomes. In 2021, 28 percent of low-income women in the paid labor force said that they engaged in app-based gig work in the past year, nearly double from 15 percent in 2020; similarly, the share of moderate- to higher-income women who engaged in app-based gig work doubled from 2020 to 2021. (See Figure 4(a).)

Figure 4(a): Share of women employed in app-based gig work has increased across income groups.

Widespread job loss, coupled with increasing need for flexible schedules due to childcare concerns, may have pushed more women into nonstandard work arrangements.

Low-income working women were twice as likely as those with moderate to higher incomes to be financially dependent on app-based gig work as their main source of income. Comparing data from 2021 and 2019, the two years when respondents were asked if app-based gig work was their primary source of income, Figure 4(b) shows that in 2021, 12 percent of low-income working women reported app-based gig work as the primary source of their income vs. 6 percent of moderate-to-higher-income working women. A rising share of working women across incomes are using earnings from app-based work as a secondary income source.

Figure 4(b): Significant rise in the share of low-income women who participated in app-based gig work

There was a notable increase in app-based gig work among mothers in the paid labor force, especially those with low incomes

Since 2019, the share of mothers in the paid labor force who engaged in app-based gig work has increased from 22 percent to 29 percent (see Figure 4 (c)). Among low-income mothers in the workforce, nearly a third—32 percent—said that they participated in app-based gig work in the past year, more than double the 15 percent who said they participated in app-based gig work in 2020, and 8 percentage points higher than the rate in 2019 (data not shown). The observed increase was largely driven by mothers who have turned to gig work as a secondary source of income: the share of low-income working mothers who chose gig work to supplement their incomes had risen from 13 percent in 2019 to 22 percent in 2021.

Figure 4(c): Increasing share of mothers turning to app-based gig work to supplement their incomes.

Benefits and Assistance

Women with moderate to higher incomes were much more likely than those with low incomes to receive important workplace benefits and protections

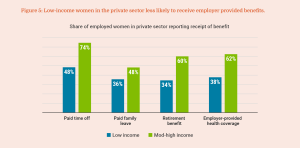

Alongside the rise of precarious, nonstandard work arrangements like app-based gig work, which reinforce economic insecurity, low-income women continue to face challenges accessing critical workplace benefits like health insurance and retirement benefits, as well as workplace protections such as paid leave. When it comes to employer-provided health coverage, 62 percent of moderate to higher income New York City women working in the private sector said that they received health insurance coverage from their employers, in contrast to just 38 percent of those with low incomes.

Similarly, 60 percent of moderate to higher income women working in the private sector said that they received retirement benefits from their employer, in contrast to just 34 percent of those with low incomes. These income disparities also extend to paid leave—which, since New York State’s paid family leave law covers most private sector workers, indicates a troubling lack of outreach and education to workers as well as gaps in accessibility.

Figure 5: Low-income women in the private sector less likely to receive employer provided benefits.

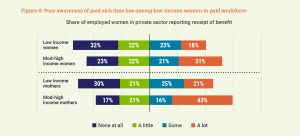

Over half of low-income women have not heard about their right to paid sick time

More than seven years after New York City’s paid sick time law took effect, a remarkably high percentage of low-income women in the paid labor force still haven’t heard about their right to paid sick leave, undermining the law’s effectiveness. Over half (55 percent) of low-income women have heard little to nothing about the city’s paid sick time law, compared to 45 percent of those with moderate to higher incomes. Among mothers in the paid workforce, 51 percent of low-income working mothers haven’t heard about the law, compared to 38 percent of mothers with moderate to higher incomes.

Lack of awareness of the paid sick time law can prevent low-income women in the paid workforce—those who can least afford to take time off without pay—from exercising their rights under the law. Among women covered under the paid sick time law, 63 percent of low-income women covered under the city’s paid sick time law said that they received paid time off for sickness or vacation, compared to 88 percent of those with moderate to higher incomes. Furthermore, since enforcement of our city’s workplace laws are largely complaint-driven, women unaware of their right to paid leave are much less likely to file a complaint against their employer.

Figure 6: Poor awareness of paid sick time law among low-income women in paid workforce

A temporarily expanded social safety net provided some relief for women who lost employment income in household

Emergency relief, such as the stimulus payments and expanded unemployment benefits authorized through the federal CARES Act in late March 2020, were intended to help ease the economic pain of millions of Americans who lost their jobs or faced pay cuts due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the Unheard Third Survey shows that the majority of women across incomes who experienced loss of employment in their household received federal stimulus checks (65-66 percent). Furthermore, nearly a third (31 percent) of low-income women who lost employment income noted that they were able to access expanded SNAP benefits, and 62 percent were enrolled in Medicaid or the NY State of Health Marketplace’s Essential Plan.

However, moderate to higher income women had more success than low-income women when it came to accessing unemployment insurance benefits: Among women with household job loss, nearly half (46 percent) of moderate to higher income women said they received unemployment benefits, compared to just 34 percent of low-income women who did.

| Table 1: Percentage of women with loss of household employment income who reported receipt of aid | |||

| Type of aid | Low income | Mod-high income | All incomes |

| Federal stimulus | 66% | 65% | 65% |

| Unemployment Insurance | 34% | 46% | 42% |

| Excluded Workers Fund | 6% | 8% | 7% |

| Expanded SNAP (PEBT) | 31% | 11% | 18% |

| ERAP | 7% | 6% | 6% |

| Delay in rent/mortgage payments | 10% | 18% | 15% |

| Reduction in rent/mortgage payments | 9% | 12% | 11% |

| Public assistance (cash assistance, TANF) | 27% | 12% | 18% |

| Medicaid/Essential Plan | 62% | 32% | 43% |

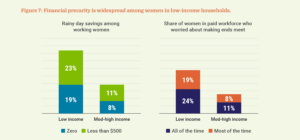

Financial instability is more prevalent among low-income women in the paid workforce

Many low-income women in the paid labor force are living on the margins and struggling to accumulate a financial cushion in the case of unexpected economic shocks such as a job loss or an emergency room visit. Low-income working women are twice as likely to have zero to less than $500 in emergency savings compared to their higher income counterparts (42 percent vs. 19 percent of moderate to higher income women.) Low-income working women are twice as likely as their higher-income counterparts to be worried all or most of the time about having enough income to pay their bills (43 percent vs. 19 percent).

Many low-income women in the paid labor force are living on the margins and struggling to accumulate a financial cushion in the case of unexpected economic shocks such as a job loss or an emergency room visit. Low-income working women are twice as likely to have zero to less than $500 in emergency savings compared to their higher income counterparts (42 percent vs. 19 percent of moderate to higher income women.) Low-income working women are twice as likely as their higher-income counterparts to be worried all or most of the time about having enough income to pay their bills (43 percent vs. 19 percent).

Figure 7: Financial precarity is widespread among women in low-income households.

Policy Recommendations

The findings of the Unheard Third Survey make clear that urgent action is needed to ensure that low-income women in New York City have the support they need at work, both as the pandemic continues and in order to rebuild for the future. The following city- and state-level recommendations are aimed at addressing this ongoing crisis.

Expand outreach, education, and enforcement of New York City and New York State laws safeguarding workers’ rights and modernize employer notice requirements

New York State and New York City have some of the strongest worker-protective laws in the nation, but they are only helpful to workers to the extent that they are able to make real use of them—that is, to the extent that workers are informed of their rights and to the extent that their rights are meaningfully enforced.

Data from the Unheard Third Survey in the previous section of this report clearly indicates that low income working women are not aware and have not been able to fully access their rights, specifically the New York City Earned Safe and Sick Time Act (ESSTA), New York State’s paid sick time law, and New York State’s paid family leave law.

Nearly six in 10 women who are covered by the New York City Earned Safe and Sick Time Act (ESSTA)7 had heard little to nothing about the law, which provides covered workers with job-protected time off from work that can be used for a number of purposes, including prenatal appointments and other reproductive healthcare, caring for a sick child or other loved ones, and when the worker is a victim of domestic violence. And unfortunately, many workers throughout the state also have yet to learn about New York State’s paid sick time law, passed in 2020 and fully effective as of January 1, 2021.8 The new state law basically follows the city law but adds time that workers are entitled to if they work for larger employers.

Only 36 percent of low-income women and 46 percent of moderate- to high-income women working in New York City’s private sector reported having access to paid leave, despite the fact that New York State’s paid family leave program covers most private-sector workers, and many workers reported leaving the workforce during the pandemic due to the need to care for themselves or loved ones. Taken together, this suggests that workers are not adequately informed about their rights to paid family leave, paid sick time, and reasonable accommodations for disability or pregnancy.

For these important rights to be meaningful, workers must be adequately informed of their rights.

To address these concerns:

- The City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection and Department of Human Rights and the State Department of Labor and Division of Human Rights, which enforce the respective paid sick time laws and human rights laws, and the State Worker’s Compensation Board, which enforces the paid family leave law, must immediately prioritize strong outreach and education campaigns to ensure that workers are well-informed about their rights, alongside strong enforcement of worker-protective laws to ensure that workers are able to meaningfully benefit from these rights. City and State agencies must work together and in collaboration with community partners to ensure that New York workers understand the full range of protections available to them under city, state, and federal law.9

- The New York City Council and New York State legislature should also enact legislation to modernize notice requirements to ensure that employers in the modern workplace—and especially the pandemic workplace—adequately inform their employees of their rights. This includes ensuring that workers are given easily-accessible, digital information about their rights and about the policies that apply to them (like the overly-rigid, punitive attendance policies discussed below) and ensuring that workers are able to access that information both in and out of the workplace. Without such requirements in place, many low-wage workers in particular have little access to the workplace policies that directly affect them. The New York City Council and New York State legislature should also consider legislation creating an annual grant program for advocacy organizations to conduct outreach and education to the most vulnerable workers, including low-income workers and those for whom English is not the primary language.

Ensure workers have increased access to fair and flexible schedules alongside standard workplace protections and employer-provided benefits

The pandemic has revealed the many ways in which the workplace can adapt to changed schedules and extraordinary events, expanding our collective imaginations about what is possible for workers going forward. Ensuring that workers have access to fair and flexible schedules is a necessary part of an equitable response to the pandemic and to ensuring that workers are able to balance competing demands into the future.

UHT data suggests that flexibility has been not merely helpful, but absolutely necessary for many women. Yet flexibility has not been equally accessible to all women in the paid labor force. Among mothers who said that they needed to stop working for reasons other than temporary or permanent job loss, 59 percent cited childcare concerns as a reason. Low-income women were twice as likely to report that they needed to stop working compared to moderate- and higher-income women—perhaps because more than half of moderate- and higher-income women were able to transition to remote work, compared to just 35 percent of low-income women.

Many workers who have been working from home successfully are navigating onerous return-to-office policies set by their employers, and workers, including those who have been working in person throughout the pandemic, are navigating the increased caregiving needs that surfaced in the last several years. We recommend these urgent actions to ensure that workers have equitable access to the fair schedules and flexibility they need.

The City should increase outreach and expand the protections of the City’s existing Temporary Schedule Change law.10 While the Temporary Schedule Change law was a groundbreaking step towards meaningful flexibility in scheduling, we need outreach, education, and enforcement to ensure that its promise is realized. Further, the City Council should expand the Temporary Schedule Change law to ensure that New York City workers have the full spectrum of protections they need, including an expanded right to receive temporary and permanent schedule changes without penalty. This should include expanding access to temporary schedule changes beyond the two days currently allowed by the law.

The City should increase outreach and expand the protections of the City’s existing Temporary Schedule Change law.10 While the Temporary Schedule Change law was a groundbreaking step towards meaningful flexibility in scheduling, we need outreach, education, and enforcement to ensure that its promise is realized. Further, the City Council should expand the Temporary Schedule Change law to ensure that New York City workers have the full spectrum of protections they need, including an expanded right to receive temporary and permanent schedule changes without penalty. This should include expanding access to temporary schedule changes beyond the two days currently allowed by the law.

Likewise, the State legislature should lead the nation by passing legislation to ensure workers—especially those who are balancing caring for their own health or the health of loved ones and maintaining their economic security—have better access to alternative schedules, including telecommuting and part-time work, as well as occasional emergency schedule changes without penalty.

Modernize the state’s Temporary Disability Insurance and Paid Family Leave program

New York State has long been a pioneer in providing temporary disability insurance and paid family leave benefits. During the pandemic, this law was more crucial than ever given heavily increased care needs. Still, the Unheard Third data makes clear that improvements to the temporary disability and paid family leave program are urgently needed to meet the needs of workers.11

New York’s temporary disability insurance benefit, which provides monetary benefits to those who are unable to work due to their own serious health needs, needs urgent improvements. Paid family leave, which covers the need for leave to care for a new child or a seriously ill loved one, provides a substantial monetary benefit and necessary employment protections, such as the right to reinstatement following leave and the right to maintain health insurance while on leave. However, New York’s temporary disability insurance benefit12 lags far behind. Temporary disability insurance benefits are capped at $170 per week—an amount that has not increased since 1989, and one which is far too low to provide the kind of support that workers, especially low-wage workers, need in today’s economy. At the same time, temporary disability insurance lacks crucial employment protections, including the right to return to one’s job following leave.

Ensuring that temporary disability insurance matches paid family leave’s benefit amount and employment protections is crucial to ensuring that New Yorkers, especially low-income New Yorkers, are able to care for their own health without sacrificing their economic well-being in the process.

Paid family leave should also be updated so that it matches temporary disability insurance’s level of portability—meaning the ability to carry benefits from one job to another and receive benefits during periods of unemployment.

Even before the pandemic, women in New York City consistently had lower participation in the labor force and lower rates of unemployment compared to men, indicating that many were unable to look for work, likely due to caregiving responsibilities. Women who are not working or looking for work because they are caring for a seriously ill child or family member, or bonding with a new baby are unlikely to be eligible for unemployment benefits; without portable, accessible paid family leave benefits, they are also ineligible for the paid family leave benefits for which they paid. Movement from one job to another, and time unemployed between jobs, has become an unfortunately typical feature in many women’s working lives during the pandemic, making portable paid family leave benefits a particularly urgent need.

Finally, the increasing importance of gig work for women during the pandemic indicates that many women are in jobs where they are considered “self-employed.” Self-employed workers can opt into the paid family leave program. However, there is an onerous two-year waiting period before they can access benefits dissuading many workers from doing so. That two-year requirement should be changed to allow immediate access to benefits.

Expand access to high-quality, affordable childcare

The Unheard Third Survey data demonstrates that among mothers who needed to stop working during the pandemic, a staggering 59 percent cited childcare needs as a reason. But even before the pandemic, childcare was a significant barrier to women’s labor force participation and economic stability. Pre-pandemic, women who were single heads of households with children were less likely to be in the labor force than their single male counterparts or their married female counterparts. At the same time, pre-pandemic, households with children headed by single women brought in significantly less income than households with children headed by single men or by two parents, leaving single mothers in a particularly precarious financial position. Women cannot economically recover from the effects of the pandemic without access to affordable, high-quality childcare and a return to the pre-pandemic status quo is unacceptable.

The State and City should act immediately to ensure that State childcare funds allotted in the 2022 budget—an amount that represents crucial but insufficient support for the industry—are used to set a standard for childcare affordability and increase access to childcare subsidies, including through use of federal childcare stabilization funds. Subsidies should be set at rates that acknowledge the true cost of high-quality childcare. At the same time, the State and City must take bold action to ensure that available state and federal childcare funding is used to increase the wages and capacity of childcare workers, including through use of federal childcare stabilization funds, and should act to end childcare deserts and ensure that access to childcare is equitable throughout New York.13

The State and City should act immediately to ensure that State childcare funds allotted in the 2022 budget—an amount that represents crucial but insufficient support for the industry—are used to set a standard for childcare affordability and increase access to childcare subsidies, including through use of federal childcare stabilization funds. Subsidies should be set at rates that acknowledge the true cost of high-quality childcare. At the same time, the State and City must take bold action to ensure that available state and federal childcare funding is used to increase the wages and capacity of childcare workers, including through use of federal childcare stabilization funds, and should act to end childcare deserts and ensure that access to childcare is equitable throughout New York.13

Curb the use of overly-rigid, punitive attendance policies

This report’s analysis of the American Community Survey data clearly demonstrates that low-income women are concentrated in particular industries: 30 percent of low-income women work in healthcare and 22 percent work in restaurant, food service, and food delivery. The industries with higher concentrations of low-income workers are also the industries in which employers often impose overly-rigid, punitive so-called “no fault” attendance policies, as documented in A Better Balance’s recent report, Misled and Misinformed: How Some U.S. Employers Use “No Fault” Attendance Policies to Trample on Workers’ Rights.14

Under “no-fault” attendance policies, workers accumulate “points” or “occurrences” whenever they miss work or arrive late, with discipline or even termination resulting after a certain number of points are accrued—a seemingly-neutral practice that in effect punishes workers for medical emergencies and tramples on their legal rights. A Better Balance’s analysis found that these policies, employed by many of the nation’s largest private employers, frequently mislead and misinform workers about their legal rights to time off without punishment by, for instance, implying that workers will receive points if they take time off while sick without reference to their rights under city and state sick time laws. This is a cruel practice that is often implemented in ways that flout existing laws. These policies and practices are also particularly dangerous in an ongoing pandemic, pressuring workers to go to work when they are sick or have been exposed to Covid-19 because they cannot afford to accrue a point and risk their economic security. To ensure an equitable recovery, stop the spread of Covid-19, and create workplaces in which workers’ rights are respected going forward, the use of these abusive policies must be addressed.

Under “no-fault” attendance policies, workers accumulate “points” or “occurrences” whenever they miss work or arrive late, with discipline or even termination resulting after a certain number of points are accrued—a seemingly-neutral practice that in effect punishes workers for medical emergencies and tramples on their legal rights. A Better Balance’s analysis found that these policies, employed by many of the nation’s largest private employers, frequently mislead and misinform workers about their legal rights to time off without punishment by, for instance, implying that workers will receive points if they take time off while sick without reference to their rights under city and state sick time laws. This is a cruel practice that is often implemented in ways that flout existing laws. These policies and practices are also particularly dangerous in an ongoing pandemic, pressuring workers to go to work when they are sick or have been exposed to Covid-19 because they cannot afford to accrue a point and risk their economic security. To ensure an equitable recovery, stop the spread of Covid-19, and create workplaces in which workers’ rights are respected going forward, the use of these abusive policies must be addressed.

Both the City and State legislatures should enact legislation aimed at curbing the use of these policies to flout workers’ rights.15

Expand app-based gig workers’ rights

Some of the most striking findings from the Unheard Third Survey related to the prevalence of app-based gig work among women workers. Across the board, participation in app-based gig work increased, with an especially notable increase in participation among mothers. With the rise in app-based gig work, many workers also face difficulty accessing the workplace rights and protections they need. Given the increase in this type of work, especially among many of the most vulnerable workers, action to address this issue is immediately necessary.

In New York, many app-based gig workers should be classified as legal employees with access all of the rights and benefits that employment entails, including paid sick time, reasonable accommodations for pregnancy and disability, protections from discrimination, paid family leave, and minimum wages. However, app-based gig companies largely misclassify them as independent contractors. While independent contractors have broad anti-discrimination protections under both state and city law,16 they lack many of the protections enjoyed by traditional employees—which means that when app-based gig workers are wrongly misclassified as independent contractors, they are at risk of losing out on many important protections.

In New York, many app-based gig workers should be classified as legal employees with access all of the rights and benefits that employment entails, including paid sick time, reasonable accommodations for pregnancy and disability, protections from discrimination, paid family leave, and minimum wages. However, app-based gig companies largely misclassify them as independent contractors. While independent contractors have broad anti-discrimination protections under both state and city law,16 they lack many of the protections enjoyed by traditional employees—which means that when app-based gig workers are wrongly misclassified as independent contractors, they are at risk of losing out on many important protections.

To ensure that app-based gig workers are able to meaningfully benefit from the full spectrum of workplace rights and protections, City and State enforcement agencies should proactively enforce existing laws to counter the trend towards misclassification. The State legislature should clarify and strengthen the legal standards for employee status17 to make it easier for workers to access the rights and protections of employees in practice and all new labor laws passed should be drafted so as to apply to those in non-standard work situations as well as those traditionally classified as employees.

Ensure caregivers are not discriminated against in the workplace

The pandemic’s particularly pernicious effects on caregivers has been widely documented, but the UHT data in this report makes this incredibly vivid, specifically data that shows that mothers and fathers were forced to stop working due to childcare responsibilities. Beyond the need for increased access and resources for childcare, the pandemic brought to light the many different kinds of caregiving needs, from the need to care for children who were themselves sick with Covid-19 or isolating after a possible exposure in or closing of schools and childcare facilities to the need to care for immunocompromised loved ones. Childcare will always need to coexist alongside family caregiving, and solutions to the employment crisis facing parents during the pandemic must account for both needs.

To that end, the State legislature must expand the familial status anti-discrimination provision of the Human Rights Law to cover the full spectrum of caregivers, and both the City Council and State legislature should consider legislation to expressly provide caregivers with a limited right to reasonable accommodations absent undue hardship to the employer and protection from retaliation for requesting accommodations based on caregiving needs to better enable caregivers to manage the demands of caregiving while working in the paid labor force. The City Council should also ensure that refusing to engage in the interactive process when a caregiver requests a reasonable accommodation under existing City law, that refusal constitutes an independent violation of the City Human Rights Law.

New York City and State should lead by example as model employers

Perhaps more than anything, the data from the Unheard Third Survey make clear that the economic upheaval that began at the start of the pandemic in 2020 has, like the pandemic itself, not abated.

In this turbulent time for both workers and businesses, the City and State government are uniquely positioned to lead by example; businesses look to the City and State government for guidance and that guidance can be provided both through formal means and broadly-applicable policy decisions, as described above, and more informally, through the model the City and State government set as employers. The City has fallen far short of that goal to date.

A 2016 report by then-New York City Public Advocate Letitia James found that the gender wage gap for women in the municipal workforce is three times larger than that faced by women in the city’s private sector,18 indicating the City’s failure to support women in its workforce. City workers are not covered by many important worker-protective laws, including ESSTA and the temporary schedule change law discussed above, and they are not automatically covered by the state’s paid family leave and temporary disability insurance programs (public employers can, but do not have to, opt to cover their employees and public-sector unions can opt in to paid family leave as part of the collective bargaining process). The City has not stepped up to provide the municipal workforce with comparably protective policies. For example, the City’s overly rigid and confusing return-to-office policy has so far fallen short of the goal of serving as a model employer.19 Importantly, the City Human Rights Law does apply to the municipal workforce, and expansions of that law—such as the recommended expansion to ensure that caregivers have the right to request accommodations without retaliation discussed above—will provide important additional protections for these workers.

A 2016 report by then-New York City Public Advocate Letitia James found that the gender wage gap for women in the municipal workforce is three times larger than that faced by women in the city’s private sector,18 indicating the City’s failure to support women in its workforce. City workers are not covered by many important worker-protective laws, including ESSTA and the temporary schedule change law discussed above, and they are not automatically covered by the state’s paid family leave and temporary disability insurance programs (public employers can, but do not have to, opt to cover their employees and public-sector unions can opt in to paid family leave as part of the collective bargaining process). The City has not stepped up to provide the municipal workforce with comparably protective policies. For example, the City’s overly rigid and confusing return-to-office policy has so far fallen short of the goal of serving as a model employer.19 Importantly, the City Human Rights Law does apply to the municipal workforce, and expansions of that law—such as the recommended expansion to ensure that caregivers have the right to request accommodations without retaliation discussed above—will provide important additional protections for these workers.

To better understand what else city workers need, the City Comptroller should undertake an investigation into the municipal workforce to uncover the key issues facing city workers, especially those who are balancing work and the need to care for themselves or loved ones. The City should also serve as a model employer by revising its return-to-office policy to meet the needs of workers with health concerns or caregiving responsibilities and proactively ensuring that all government employees have access to paid family and medical leave and reasonable caregiving accommodations, and the State should learn from the issues with the City’s current approach.

At the same time, both the City and State governments should convene task forces, similar to the City’s new ‘Future of Workers’ taskforce, made up of government officials, business leaders, members of advocacy organizations, and workers themselves to share lessons learned while working through the pandemic—which has been both an enormous challenge and an unprecedented, often successful, experiment in workplace flexibility—and develop recommendations for a way forward that works for everyone.

Conclusion

Women working in low wage jobs in New York City, especially women of color, disproportionately shoulder the burden of caring for themselves and others, and yet they lack the support they need to manage this demand—a reality that has only become clearer as the pandemic has exacerbated so many of the challenges of balancing work and caregiving. The Unheard Third Survey data makes clear that women in low-wage jobs have been struggling during the pandemic and highlights the urgent need for responses that support them and their families as the pandemic continues and build a foundation for a post-pandemic future in which their needs are truly met. Responding to their needs will require holistic solutions that address the full range of their needs.

After the pandemic began, the federal government adopted several emergency measures to assist workers, including expanded unemployment eligibility, rental assistance, and emergency sick time and family and medical leave for those with Covid-19-related needs for leave. Unfortunately, many of these measures expired in 2021. Without this assistance, and in the midst of an uncertain recovery, workers, especially women in low-income households, continue to struggle to make ends meet.

In order to ensure that women in New York City can manage the competing demands of work and care while maintaining their economic security, many of the solutions they need must necessarily focus on the workplace. To manage working and caregiving, New York City women need laws that provide them with the time, flexibility, and support they need at work. New York City and New York State have long led the way when it comes to supporting women and caregivers in the workforce and must continue to do so now. The Unheard Third Survey data outlined in this report makes clear that women urgently need more support at work; the recommendations outlined in this report provide a path forward.

In order to ensure that women in New York City can manage the competing demands of work and care while maintaining their economic security, many of the solutions they need must necessarily focus on the workplace. To manage working and caregiving, New York City women need laws that provide them with the time, flexibility, and support they need at work. New York City and New York State have long led the way when it comes to supporting women and caregivers in the workforce and must continue to do so now. The Unheard Third Survey data outlined in this report makes clear that women urgently need more support at work; the recommendations outlined in this report provide a path forward.

Survey Methodology

The Community Service Society of New York designed this survey in collaboration with Lake Research Partners, who administered the survey by phone using professional interviewers. The survey was conducted from July 8th through August 10th, 2021. The survey reached a total of 1,763 New York City residents, age 18 or older, divided into two samples. 1,110 low-income residents (up to 200% of federal poverty standards, or FPL) comprise the first sample including 533 poor respondents, from households earning at or below 100% FPL (69.4% conducted by cell phone) and 577 near-poor respondents, from households earning 101% – 200% FPL (71.1% conducted by cell phone). 653 moderate- and higher-income residents (above 200% FPL) comprise the second sample, including 389 moderate-income respondents, from households earning 201% – 400% FPL (70.2% conducted by cell phone) and 264 higher-income respondents, from households earning above 400% FPL (61.7% conducted by cell phone).

Landline telephone numbers for the low-income sample were drawn using random digit dial (RDD) among exchanges in census tracts with an average annual income of no more than $44,660. Telephone numbers for the higher-income sample were drawn using RDD in exchanges in the remaining census tracts. The data were weighted slightly by income level, gender, region, age, immigrant status, and race in order to ensure that it accurately reflects the demographic configuration of these populations. Interviews were conducted in English (1,662), Spanish (83), and Chinese (18). The low-income sample was weighted down into the total to make an effective sample of 600 New Yorkers.

In interpreting survey results, all sample surveys are subject to possible sampling error; that is, the results of a survey may differ from those which would be obtained if the entire population were interviewed. The size of the sampling error depends on both the total number of respondents in the survey and the percentage distribution of responses to a particular question. The margin of error for the entire survey is +/- 2.3%, for the low-income component is +/- 2.9%, and for the higher-income component is +/- 3.8%, all at the 95% confidence interval.

For questions related to the survey, please reach out to Emerita Torres, Vice President of Policy Research and Advocacy, at [email protected]

Appendix

All the data shown below are based on the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Samples for the years 2005 to 2019.

Figure A1: Women of color make up two-thirds of the workforce and over 80 percent of low-income women in the workforce.

Figure A2: Low-income women more likely to be immigrants.

Figure A3: Women’s Labor Force Participation rate was a full 10 percentage points lower than that of men, but women made some small gains overtime–from around 55 percent in 2005 to 60 percent in 2019. Hispanic women continue to face the most obstacles in participating in the labor market.

Figure A4: Women who are heading households with a child/children are much less likely to participate in the labor market.

Figure A5: Unemployment rates for Black and Hispanic women were consistently higher than the rates for Asian and white women.

Figure A6: Unemployment rates for Black and Hispanic women continue to be higher even among those with similar educational attainment.

Figure A7: Women continue to earn less than men, and although the gap between median wages had begun to shrink over the first few years of the decade, those trends have abated. Of note, Hispanic women continue to be paid low wages relative to non-Hispanic women as well as men.

Figure A8: Single female-headed households with children have to survive on extremely low incomes.

Figure A9: Households with a child/children headed by single Latina/x women experience a major economic disadvantage.

Figure A10: Low-income women in the paid workforce predominantly work in personal and other services, leisure and hospitality and retail trade—industries which typically pay lower wages.

Endnotes

[1] Alisha Haridasani Gupta, Covid Shuttered Schools Everywhere. So Why Was the ‘She-cession’ Worse in the U.S.?, N.Y. Times (May 28, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/us/shecession-america-europe-child-care.html.

[2] See, e.g., Congressional Res. Serv., The Covid-19 Pandemic: Labor Market Implications for Women (2020), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46632.pdf; Julie Kashen, Sarah Jane Glynn, & Amanda Novello, How COVID-19 Sent Women Backward, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Oct. 30, 2020, 9:04 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/10/30/492582/covid-19-sent-womens-workforceprogress-backward/; André Dua et al., McKinsey, Achieving an Inclusive US Economic Recovery (2021), https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/achieving-an-inclusive-us-economic-recovery#:~:text=While%2075%20percent%20of%20GDP,nine%20months%20of%20the%20pandemic.

[3] See, e.g., Morgan Smith, Black Women Have Been ‘Hit Especially Hard’ by Pandemic Job Losses—and They’re Still Behind in Recovery, CNBC (Feb. 28, 2022), https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/28/black-women-were-hit-especially-hard-by-pandemic-job-losses-and-recovery-is-lagging.html; Diane Coyle, Working Women of Color Were Making Progress. Then the Coronavirus Hit, Opinion, N.Y. Times (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/14/opinion/minority-women-unemployment-covid.html.

[4]NYC Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, New York City Government Poverty Measure 2019: An Annual Report from the Office of the Mayor (2021), To arrive at the NYCgov threshold for 1-adult, 2-children family, we multiply the reference threshold, that of a 2-adult, 2-children family, set at $36,262 by 0.830. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/opportunity/pdf/21_poverty_measure_report.pdf.

[5] The survey question on job loss in 2019 asked whether respondent or anyone on household lost their job in the past year. The 2020 and 2021 job loss rates refer to a separate question in which respondents said that they or a member of their household had been temporarily laid off or furloughed, or lost job permanently, since the start of the pandemic.

[6] Claire Ewing Nelson, Nat’l Women’s L. Ctr., All of the Jobs Lost in December Were Women’s Jobs (January 2021), https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/December-Jobs-Day.pdf.

[7] N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 20-911 et seq. For a model resource informing workers of their rights under this law, see Know Your Rights: New York City Paid Sick Time, A Better Balance (last visited May 24, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/know-your-rights-new-york-city-paid-sick-time/.

[8] N.Y. Lab. L. § 196-b. For a model resource informing workers of their rights under this law, see Know Your Rights: New York State Paid Sick Time, A Better Balance (last visited May 24, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/know-your-rights-new-york-state-paid-sick-time/.

[9] For a model of a resource that provides comprehensive information about local, state, and federal rights, see Know Your Rights: New York, A Better Balance (last visited May 23, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/states/new-york/.

[10] NYC Admin. Code §§ 20-1261 et seq. For more information on fair scheduling laws throughout the country, see A Better Balance, State and City Laws and Regulations on Fair and Flexible Scheduling (updated January 14, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/fact-sheet-state-and-city-laws-and-regulations-on-fair-and-flexible-scheduling/.

[11] For information about New York State legislation aimed at addressing this issue, see Building the Paid Family and Medical Leave New Yorkers Need: A9479/S8735 Bill Explainer, A Better Balance (last visited May 25, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/building-the-paid-family-and-medical-leave-new-yorkers-need-a9479-s8735-bill-explainer/; Building the Paid Family and Medical Leave New Yorkers Need Will Help Vulnerable Communities, A Better Balance (last visited May 25, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/fact-sheet-building-the-paid-family-and-medical-leave-new-yorkers-need-will-help-vulnerable-communities/.

[12] N.Y. Workers’ Comp. Law §§ 200 et seq.

[13] Letter from Empire State Campaign for Childcare to Kathy Hochul (Sept. 8, 2021), https://scaany.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Empire-State-Campaign-for-Child-Care-Fall-Priorities-Sept-2021_Final.pdf.

[14] Dina Bakst, Elizabeth Gedmark, & Christine Dinan, A Better Balance, Misled and Misinformed: How Some U.S. Employers Use “No Fault” Attendance Policies to Trample on Workers’ Rights (2020).

[15] For information about New York State legislation aimed at addressing this issue, see Why New York Needs a Law Protecting Employees From Being Punished for Lawful Absences, A Better Balance (last visited May 24, 2022), https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/fact-sheet-why-new-york-needs-a-law-protecting-employees-from-being-punished-for-lawful-absences/.

[16] See A Better Balance, State Leadership on Anti-Discrimination Protections for Independent Contractors (April 22, 2020), https://www.abetterbalance.org/state-leadership-on-anti-discrimination-protections-for-independent-contractors/.

[17] See Jenny R. Yang, Molly Weston Williamson, Shelly Steward, K. Steven Brown, Hilary Greenberg, & Jessica Shakesprere, Reimagining Workplace Protections: A Policy Agenda to Meet Independent Contractors’ and Temporary Workers’ Needs 6 (2020), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103331/reimagining-workplace-protections_0.pdf.

[18] Letitia James, N.Y.C. Public Advocate’s Office, Policy Report: Advancing Pay Equity in New York City 2 (2016) (on file with A Better Balance).

[19] Letter from A Better Balance to Mayor Bill de Blasio (Sept. 21, 2021), https://www.abetterbalance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Letter-to-NYC-Mayor-re-Return-to-Office_FINAL.pdf.